Open banking and payment system modernization can help lower swipe fees

DISCLAIMER: Articles are written to reflect the interests and views of the author(s), and are not intended as an official Payments Canada statement or position.

With the right upgrades to Canada’s payments scene, we can lift the fence around billion-dollar bills on the sidewalk.1

Late last year, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced a number of platform commitments at an event in the Trois-Rivières riding of Quebec. Among other promises to help small- and medium-sized businesses, he said his government would eliminate swipe fees on the HST- and GST-portions of credit-card transactions. According to the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, the move would save Canadian businesses $500 million a year.

Though the announcement was warmly welcomed by the business community, the savings aren’t huge. It’s been estimated that, in Canada, credit card networks and issuer banks collect nearly $5 billion a year in swipe fees, all of which come from merchants, and some of which go to consumers in the form of loyalty points and cash rewards. A longstanding source of tension between merchants and credit card networks, Wal-Mart decided to stop accepting Visa credit cards for a short time in 2016 because it was costing them alone hundreds of millions of dollars every year.

Ottawa appears to sympathize with businesses, but regulating swipe fees is a messy affair. These fees are great for credit card networks and issuer banks, for whom swipe fees generate revenue. They’re even great for some consumers who collect more rewards than their fees and interest payments cost them. But they’re not as great for merchants, who pay for everyone else’s slice of the pie.

It’s a political quagmire, which is partly why it’s so difficult for the federal government to regulate them. The federal government announced its latest voluntary agreement with Visa, Mastercard, and American Express to lower interchange fees in 2018, but the change was small: from 1.5 percent of the whole transaction value to 1.4 percent, or just a tenth of a percentage point.

Despite the federal government’s best efforts, swipe fees are still high if you ask some merchants.

On the bright side, regulating them isn’t the only way to put downward pressure on them. There’s also consumer-directed payments, which, when coupled with an open, real-time payments platform, could give consumers and merchants a wider range of attractive payment options — including some that could be competitive at the point-of-sale, where credit cards are widely used.

It might sound like a lot to take on, but the foundational technological and regulatory change is already underway: payment system modernization and the federal government’s work on open banking, which it recently rebranded as “consumer-directed finance.”

...

According to the 2019 Canadian Payment Methods and Trends report, credit cards accounted for about a third of all transactions in 2018. They also accounted for more of the payments value than all other payment methods combined at the point-of sale. Credit cards have been growing faster than debit cards as a payment method, mostly due to credit card rewards and the rise of e-commerce, where they’re the preferred method of payment.

Every time you make a payment with your credit card, a long and costly sequence happens behind the scenes. Given the speed with which transactions are executed — a matter of seconds — some have even described it as a modern marvel.

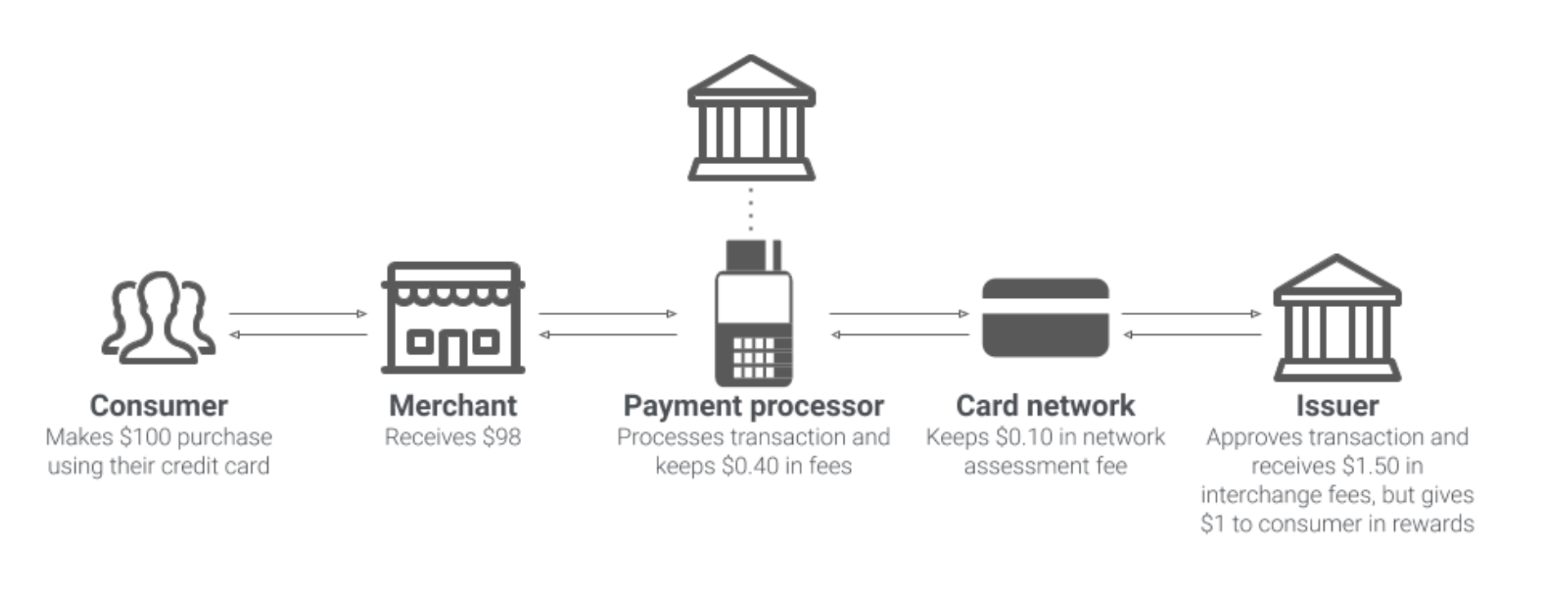

And it is. First, the cardholder inserts or taps when they’re presented with a terminal at the point-of-sale, or they enter their card credentials in an e-commerce check-out gateway. The terminal is provided by the acquiring bank or a payment processor, which routes the payment information through the credit card network to the issuer bank for approval. When the issuer approves the transaction, the response code is sent back through the network to the acquiring bank or its processor. Then the confirmation shows up on the point-of-sale terminal or the e-commerce check-out portal. All of this happens in a matter of seconds. Settlement of funds happens later, but both consumer and merchant can be satisfied that the transaction will result in a payment and conclude their interaction.

Modern marvels aren’t cheap. Across the payment flow, fees are collected for each of the services provided. In addition to the routing and central clearing services that command a fee, issuer banks provide credit that doesn’t come free. When you pay by credit card, your issuer bank is fronting you the money to buy your goods and services. To make sure everyone across the payment flow is compensated, fees are paid on every transaction.

Figure 1. How fees are distributed across the payment flow (source: external consultants)

...

Merchants bear the brunt of these fees because of the economics of the retail payments market, which is a canonical example of what’s called a two-sided market. As economist Marc Rysman of Boston University wrote in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, “Payment cards like Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are two-sided in the sense that they require consumer usage and merchant acceptance to be successful.”

Successful firms in two-sided markets — or platforms, as they’re sometimes called — solve a chicken-and-egg problem when courting the different sides of their market. Without any consumers aboard, the platform won’t be of any value to merchants. And with no merchants, it won’t be of any value to consumers. So what does the platform do? Jean Tirole, a pioneer in the economics literature on two-sided markets, uses the metaphor of a see-saw to explain:

"If one side of the market benefits a lot from interactions with the other side, then the platform can charge more to the former and, in a “seesaw” pattern, will want to charge less to the latter side to make it more attractive to join. The platform thus needs to know which side of the market is most interested in the service (has the lowest elasticity of demand, and is therefore likely to pay more without ceasing to consume), and which side brings more value to the other."

Nearly half of small- to medium-sized businesses accept card payments, including credit cards, because they believe they wouldn’t make sales if they didn’t.2 A Bank of Canada survey reached the same conclusion. From the merchant’s perspective, the chance a consumer chooses to shop somewhere else, rather than forego their credit card rewards, is high enough that the expected cost of not accepting credit cards (and losing the sale) is higher than that of accepting them (and getting the sale). This means that merchants have the lower elasticity of demand.

The result is that merchants are charged the highest prices and consumers the lowest. In some cases, consumers are actually paid more in the form of loyalty points and cash rewards to use the card than they’re charged in annual fees and interest. This is the result of aggressive competition between issuer banks for consumer usage, and the interchange revenue it brings in.

Intense competition is usually considered a good thing, but it’s not always a good thing in two-sided markets. According to Rysman, competitive pricing on one side of the market can translate into monopolistic pricing on the other:

"It is because the intermediary can be viewed as a monopolist over access to members that do not use other intermediaries. Hence, firms compete aggressively on the side that uses a single network in order to charge monopoly prices to the other side that is trying to reach them … As a result, competition between platforms can have large price effects on the side of the market that uses a single platform and little or no effect on the side that uses multiple platforms. This result might explain why payment card pricing has increasingly favored consumers over time rather than merchants (for instance, with the rise of rewards programs), since consumers and not merchants typically use a single network and competition among card networks has become more important relative to competition between card networks and cash."

…

Some people worry that these market structures aren’t competitive enough. Two-sided markets oftentimes “tip” towards a dominant player or handful of players due to economies of scale and network externalities. The worry is that without competitors, companies can charge high prices and keep out would-be innovators.

Having just a few providers isn’t necessarily bad, though. In many cases, more than a handful of intermediaries would be unnecessary and cause more confusion than anything else. The value of an intermediary lies in its ability to connect as many people as possible. It doesn’t make sense to have 20 competing payment systems, just as it doesn’t make sense to have 20 competing versions of the internet.

Instead of trying to figure out what the right number of intermediaries is, policymakers should try to make the market as contestable as possible, and then let the market do the rest itself. Here is Tirole again:

"Monopolies are not ideal, but they deliver value to the consumers as long as potential competition keeps them on their toes. They will then be forced to innovate and possibly even to charge low prices so as to preserve a large installed base and try to make it difficult for the entrants to dislodge them. But for such competition to operate, two conditions are necessary: Efficient rivals must, first, be able to enter and, second, enter when able to."

The retail payments market might not be contestable by this criteria. Entry, exit, and switching costs are naturally very high in the case of a payment system.

While there has been some entry by new players in the payments space, it has been on the peripheries. Using Amazon’s one-click payment or adding your credit card details to the Uber app makes the consumer experience convenient, offering a seamless checkout experience. Merchants and businesses also benefit. Shopify Pay has increased checkout speeds by 40% and sales conversion rates for returning customers by 18% using stored payment credentials. It’s also easier and cheaper for smaller merchants to accept card payments thanks to new players like Square.3

Many of these innovations rely on the existing card networks behind the scenes, rather than on establishing their own payment systems. They feel like new and innovative ways to pay, but they mostly rely on old ways to pay.

Today new players in the ecosystem compete with banks, but also rely on them to access core payment systems, credit card networks and others. This raises a question about how contestable retail payments markets really are because banks are always lodged in between would-be innovators and core payment systems. As a result, there’s always the risk of the principal-agent problem materializing, if it hasn’t already.

…

Competition authorities and regulators have long wondered whether there’s a competition problem in payments, and Ottawa seems attuned to the plight of merchants. Regulating swipe fees might be too heavy-handed, as it would send a ripple of unintended consequences through a payment system that has served many Canadians well. There is, however, another way: the intersection of open banking and payment system modernization. These two initiatives, if designed and implemented with e-commerce and point-of-sale use-cases in mind, would give customers and merchants a chance to compete with credit card networks, making the retail payments market more contestable.

Imagine a world where merchants and their customers could exchange the promise of future funds without a credit card network, issuers, and acquirers in between them. A world where merchants and customers could speak directly with each other and then, with a paytech in between them, or the merchant acting as one, plug into a real-time payment system to execute the payment. Consumer-directed payments, coupled with a real-time, open payment system, could make that world a reality by cutting out the middleman, or maybe even a couple of them.

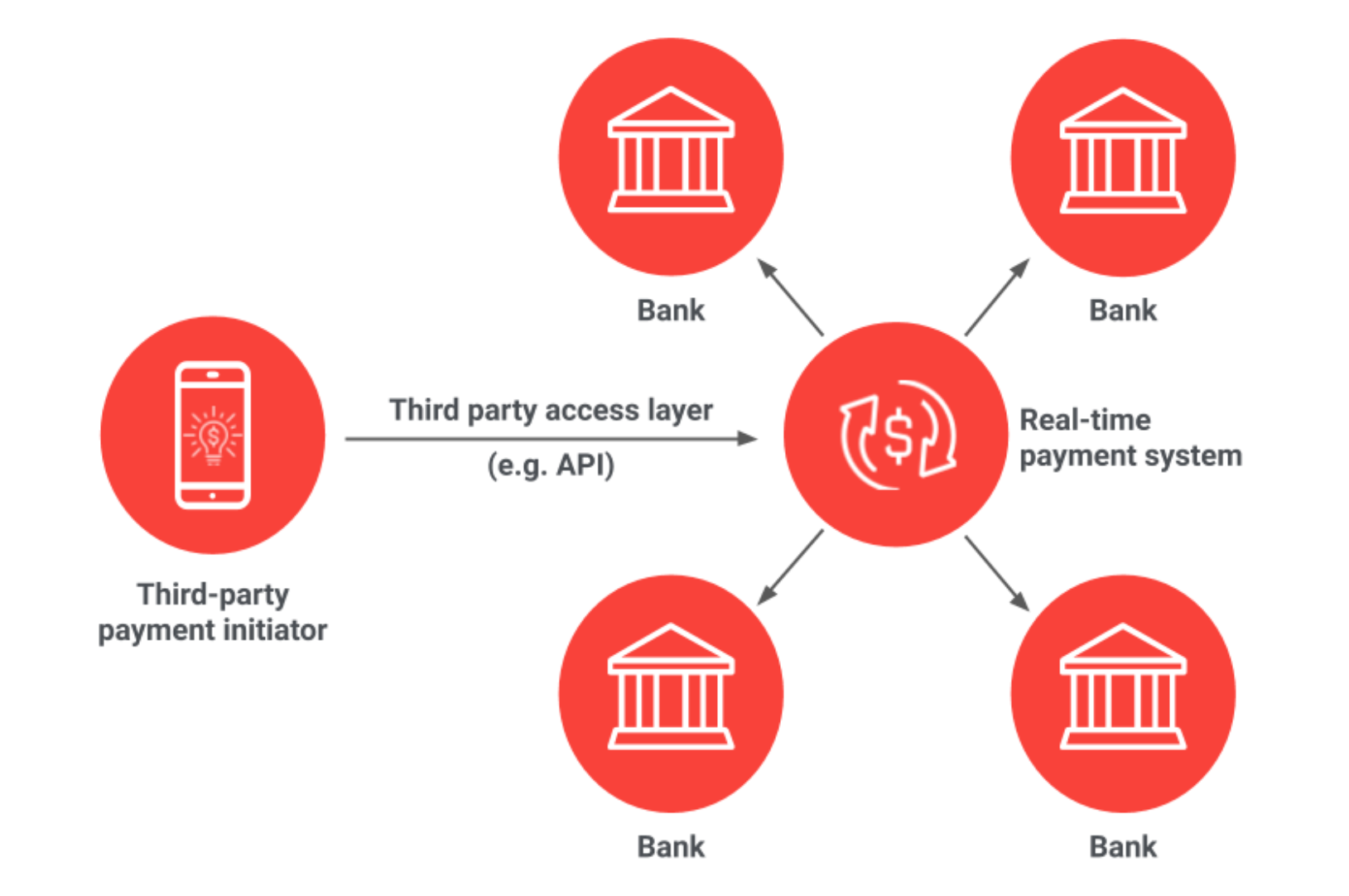

Figure 2. Payment initiation and direct payment system access

Look at what happens when new players can plug into a real-time payment system and, under a consumer-directed payments framework, initiate credits or debits from a customer’s bank account without going through a bank. Merchants or paytechs could arrange for future payments to be pushed or pulled from payors without their debit or credit card. They could arrange for immediate payments, too.

These initiatives would give innovators the chance to incentivize people away from legacy ways to pay, such as by credit card. To encourage use, merchants could offer their own loyalty or rewards programs, like the Starbucks mobile app, which could create value for them and their customers. Or innovators could bundle particular ways to pay with other services that their customers care about more than whether they pay by credit card or pre-authorized debit.

We’re already seeing such innovation outside of Canada, where open banking and real-time payment systems are more than just an idea. Adyen, a payment service provider whose customers include Uber, eBay, Spotify, and Microsoft, rolled out a payment option powered by open banking with Dutch airline KLM. The same can be done through a core payment system, as illustrated in Figure 2, which some prefer to the alternatives. We’re seeing this approach beginning to take shape in Australia, where third-party payment initiation through the core payment system is expected to come to fruition.

…

Open banking and payment system modernization should go beyond promoting innovation in the peripheries of retail payment markets. Swipe fees from credit cards in Canada are some of the highest in the world. Even with the recently announced reductions, some of which have been delayed due to COVID-19, merchants might not get the relief they want. Some merchants are worried savings won’t be passed on by payments processors, and new fees will eclipse whatever savings these reductions will generate.

These two initiatives need to revolutionize how Canadians pay. Designing and implementing them in a complementary way is crucial. Last year, the Department of Finance consulted on open banking. They asked whether consumer-directed payments should be included in the scope of open banking in Canada, adding that anything the government did on open banking would need to be staged and aligned with payment system modernization.

But there has been little talk out in the open of what exactly the “staging” and “alignment” of consumer-directed payments with payment system modernization means or ought to mean. If the ecosystem really cares about making retail payments markets more contestable, which could revolutionize how Canadians pay, it should start talking before it’s too late.

Authors

Shaun Byck

As an economist on the Research team, Shaun conducts research on policy issues related to fintech and high-value payment systems. Prior to joining Payments Canada, he worked at the Competition Bureau, where he researched the impact of fintech on innovation and competition in Canada's financial system. Shaun holds a Master's degree in economics from Carleton University.

Alexander Vronces

Working on the Policy and Regulatory Affairs team, Alex does research and gives strategic advice on matters relating to Payments Canada's mandate and public policy objectives. Before joining Payments Canada, he worked in tax controversy and transfer pricing, providing economic advice to large, multinational firms. He's also worked in public policy advocacy on matters relating to international trade. In school, Alex studied economics and journalism.

1 The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Payments Canada.

2 RFi Canada SME Banking Council H1 2019.

3 The Bank of Canada estimates that Square was used by 15% of smaller (less than $10 M in revenue and 50 employees or less) Canadian merchants accepting credit cards.